Exhibiton Essay

By Kristina Johnson

The Saint Paul Winter Carnival is one of the oldest Winter festivals in the United States. Its creation came as a response to inflammatory news reports claiming that the white tundra of Winter made Minnesota completely uninviting. James J. Hill, along with many other notable local business owners, concocted a celebration of Winter to prove them wrong. Since 1886, the Saint Paul Winter Carnival prides itself on showing off the beauty, and fun, of Minnesota winters. While it might seem ludicrous to some, this tradition has kept generations of Minnesotans from being winter hermits. Sure, it may seem intimidating when the local meteorologist proclaims that it’s colder outside your front door than it is in Antarctica, or when it snows enough to completely bury your car, but Minnesotans own these things; we don't wallow in the frozen lakes of our own misery. We are champions of the cold, the Saint Paul Winter Carnival is just one of the many reasons our winters are nothing short of great. People historically celebrate social traditions that teach us about life, where we came from, and who we are as people. Our Carnival tradition exists as a way to pass on the values, morals, customs, and culture of one generation to the next.

The legend behind the Saint Paul Winter Carnival centers around the myth of King Boreas, God of the Winds, and his wife, the Queen of Snows. They are challenged by Boreas’ greatest foe, Vulcanus Rex, the God of Fire. Boreas proclaims a Carnival of festivities in St. Paul for ten days as a response, but on the final day Vulcanus Rex storms Boreas’ ice castle with his Vulcan Krewe. In an effort to refute violence, Boreas retreats back to Olympus with his Queen, to dwell among the other gods, where he awaits the next year's reign of ice and snow. The grandiose events are adapted from an Ancient Greek myth, which symbolically iterates the dramatic change of Winter into Spring.

Over 135 years ago at its genesis, the King, Queen, and their Court were nominated from a pool of corporate sponsors to the Carnival. Today’s festivities allow for greater accessibility, wherein an incredibly diverse amount of individual and corporate volunteers participate in steering the Carnival’s multitude of events. A royal coronation is hosted every year after new positions are selected. At this ceremony, each royal individual commits to serve the City of Saint Paul and greater community by agreeing to participate in over 300 events throughout the year. A major percentage of the work Carnival royalty does takes place outside of the ten day window of Carnival events. Members of the Guard attend city meetings, host banquets, and of course, plan and organize financing for the next year's festivities. All of these local events focus around the entertainment and enrichment of the community.

In 1986, Northwest Airlines nominated my uncle, David Johnson, to serve in the Royal Guard. As someone who grew up marveling at the ice castles and attending many parades, he was thrilled to be inducted into royalty. One year he even remembered buying an ice block carved from Lake Phalen that was used to build the ice castle. 1986 happened to be the 100th year celebration of the Carnival. After the large coronation event, his royal duties took him across the country–even up to Winnipeg–to represent Minnesota at other Winter festivals and celebrations. A few years later in 1992, he became the Prime Minister, a position that is of high importance and responsible for “preparations in all the Principalities, Provinces and Royal Houses within the Realm of St. Paul.” But being any part of the Winter Carnival is a great responsibility and commitment to the community, often lasting longer than just one year. To this day, he still communicates with friends and acquaintances he made while participating in the myriad of events.

Another noteworthy tradition of the Winter Carnival is the annual treasure hunt. Daily clues appear in the St. Paul Pioneer Press and if you decode them correctly they will direct you to the Carnival medallion’s hiding place plus a nice monetary reward. The hunt is a popular Winter Carnival tradition with thousands of people participating. In today’s advanced technological age, there are online forums which debate the minutiae of the clues with participants from all over the globe. My grandmother loved the thrill of the hunt. My father recalls her eagerly awaiting each clue to see if she could decipher the cryptic text. He shared a memory of treasure hunting with her while he was in medical school at the University of Minnesota. Outside, in the frigid air, my grandmother and father were attempting to solve the latest clue, which led them right to their neighborhood park. Along with a handful of other treasure hunters, they were both on the prowl with flashlights in hand. Each step filled them with more anticipation and excitement. All of the sudden from not too far away rang the voice of someone yelling that they had found the medallion! They had indeed found it. Although defeated, it was surely a great time, and I know my grandmother was probably already looking forward to next year’s hunt.

Family, social, religious, spiritual, and secular traditions shape our upbringing. What follows from generation to generation is known as tradition. However, over time things change; improvements are made and the world evolves. The ethos of what we define as humans is an amalgamation of our struggles, fears, needs, and desires, which largely remain the same due to inherent characteristics we call human nature. Tradition becomes our subtle reminder of this, heightening the awareness of past selves or others, cultivating a sense of stability and belonging, and acting as a collective guiding force in our lives and societies. As author and lecturer Ardis Whitman wrote,

"We must cherish our yesterdays, but never carry them as a burden into the future. Each generation must take nourishment from the other and give knowledge to the one that comes after."

Whitman highlights the importance of change in tradition. Change may not always propel us forward in the sense of quantifiable social "progress,” but does propel us forward as human beings in life. Tradition nourishes us with foresight, understanding, and equips us with a heightened emotional intellect which we in turn bestow onto the future. We define tradition in many ways but it always flows from generation to generation.

A loved one's possessions are a reminder of their presence, even if they are no longer among us. A photograph could be the most cherished object you have to remember someone special. It can be difficult to make changes to a home when someone has passed. Some people are reluctant to move furniture, throw things away, or even clean up their home after a loved one has died. Many people find, in time, that leaving their loved one’s belongings fixed and unused isn’t the right answer either. Some people need to take their time, do everything at their own pace, and cannot rush. In this instance, change that happens too much too soon depletes the memories of that person. Losing the memories of something or someone cherished is, at least, equally as painful as losing the object in reality. But sadly, the reality also is that there are some items that need to be taken care of sooner rather than later and sometimes decisions, big and small, which eventually need to be made.

After my last paternal grandparent passed away in 2013, my father and his siblings sorted through their parents' belongings. Slowly my childhood home’s basement became the final resting place for boxes of legal papers, photo-albums, furniture, Schmidt Brewery ephemera, jewelry, trinkets, a self-playing piano, and many, many family portraits. There was no shortage of stuff to look through. Both of my grandparents were only children and held onto much of their respective families' treasures. My grandmother, Emily “Betty” Johnson (née Bremer), continued to collect and save nearly everything until her death in 2009; my father crowned himself the successor of this tradition, often citing that at some point an object in question could one day hold its purpose again. A rather optimistic outlook on his behalf as technology replaced a lot of the items we kept; but I thought that maybe, in his heart, he was not ready to sort through all the deeply personal memories associated with his parents belongings.

In early January of 2022, l went to my parents house to look through boxes in the basement. Cold and alone in a big house, I was searching for photographs and mementos of past Winter Carnivals to add to my exhibition. In a previous conversation, my dad mentioned that my great grandfather had shot footage of the Schmidt Brewery Marching Band from a Winter Carnival parade sometime in the 1930s. Perfect for this project, I was on the hunt–just like my grandmother searching for the Winter Carnival medallion. While on my journey I discovered many other treasures. I came across annotated photo-albums, some dated back to the early 1900s, but mainly focused on collecting pictures set in discernible Minnesota Winter settings. Among their personal belongings are pamphlets from visitor centers across the globe, coasters from bars and the Schmidt Brewery, and photographs scrawled with my grandmother’s handwriting on the back indicating who, what, where, or when the photograph was taken. These objects now exist as a testament and proof that Grandma Betty liked adding a personal commentary to much she came across. Today, many people refer to this as “hoarding,” but I perceive it to be a lot more than that. I believe my grandmother cherished the sentiment that everything matters.

My grandparents were raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, but in dramatically different neighborhoods. My grandmother's family upheld a prestigious German background in beer-making and banking. In those times, her family lived a posh, upper-class lifestyle on North River Road. As a child she lived through the kidnapping of her father, attended Wellesley College (Class of 1947), and watched the fall of her family’s historic brewery. For many years she taught at St. Paul Summit School, the same school she attended growing up. My grandfather was raised in a predominantly blue-collar Swedish neighborhood in East St. Paul. At 17, he finagled his way into the Navy and deployed to Japan aboard the S.S. Walker amidst World War II. After he came home, he attended the University of Minnesota, became a Lawyer; in the 1960s and 70s he served in the State Legislature which culminated with a run for Governor. Together my grandparents raised six children.

Folders containing generations of handwritten letters provide me with a rare glimpse into the personalities of my family members. I found pages of letters sent from great, great grandparents to my great grandparents and so on. A daunting letter dated back to 1919 was sent by my great, great grandmother, Emily Bremer (née Esswein), to my great grandfather, Edward G. Bremer, while he was away at college in Washington D.C. In nearly perfect calligraphy she wrote to him,

“You better make your mind up that your partying days are over and make up your mind to get serious about school.”

I later learned from my father that this letter was probably sent right before he got kicked out of college.

The next album I went through contained newspaper articles about my great grandfather's kidnapping. As I scanned through pages of headlines, I was reminded of the Summer of 2015. My dad and I drove down to Kansas City, Kansas, to document previously vaulted files on my great grandfather's kidnapping. These files were temporarily released by the Archive of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. On that trip, I helped my dad document original trial transcripts plus letters that my great grandfather was forced to write during his kidnapping. I knew I would remember this trip for the rest of my life. We spent hours in white gloves, carefully taking pictures, and marveling at the family history we had tracked down and now held in our hands. I learned the whole story of his kidnapping as if it were the first time, and made sure to ask my dad lots of questions about what he personally remembered of my great grandfather.

In due time, I made my way to my parents' generation, where I discovered endearing letters that my dad wrote to his youngest brother, Ricky, while he was away at Camp Foley during a Summer in the 1960s. It's quite an odd feeling to think about your parents as children, growing up in similar ways to you, revealing how their younger self matured in real time. I tried to process what I was feeling but had become overwhelmed by all the unanswered questions. My eyes spilled tears as I filled with feelings of longing, sadness, inspiration, and appreciation. Now that I had seen all of this historical family information, I understood why it's so hard to let go. Many people don’t have the luxury or means to preserve things as their loved one left them but my family has made an effort over multiple generations to do so. Everything my parents kept became priceless artifacts of my family’s history, and encapsulates memories of my lineage. I realized then that my biggest family tradition is to inherit the responsibility of preserving its history.

To unearth these memories triggered a sense of melancholic longing for the past that I had never experienced, a feeling I would describe as greater than regret. In recent years, I learned a Portuguese word and it appeared in my mind, saudade. Its definition is too complex to translate into one English word but describes one’s deepest feelings of nostalgic melancholia.

“One can feel saudade for something that once had been there, or was never there at all. One is tempted to get lost in imagination, where one meets both sorrow and consolation. All the possibilities of ‘what-if’ fill one with ‘indolent dreaming wistfulness,’ missing what one never had.”

I wish I could’ve gone through all of these belongings before my grandparents passed away. I feel a deep sadness for every memory lost to time without a documented explanation.

What started as a personal yet historic glimpse into the Winter Carnival for the George Latimer Central Library became an intensely connective experience to my family history. I am inspired and driven to make the same promise that my grandparents and parents made, which is to inherit the archive of their history and preserve it for future generations. My relatives' memories inspire me to keep chronicles of my own, while pulling from and reimagining the symbolic narratives of the past. Artistic representations of moments where I derive the most meaning become a way to archive the history of events in my life, supplemented by personal commentary. Preserving history has become a part of my artistic practice. I hope to encourage others to investigate and record their lineage, to ask loved ones questions about their past and relatives. Sporadically, I'll point to a portrait hung in my parents house and ask, “Who was that again?” Always enjoying the story that it induces. It reminds me of the sentiment my grandmother carried: everything matters. There is no moment too small. No photograph is too insignificant. No season is too forgettable. The artifacts we held dear in the span of our lifetime are all we have to be remembered by and once we are gone, they are all that’s left. You never know what kind of treasure you could be saving for someone in the future to discover.

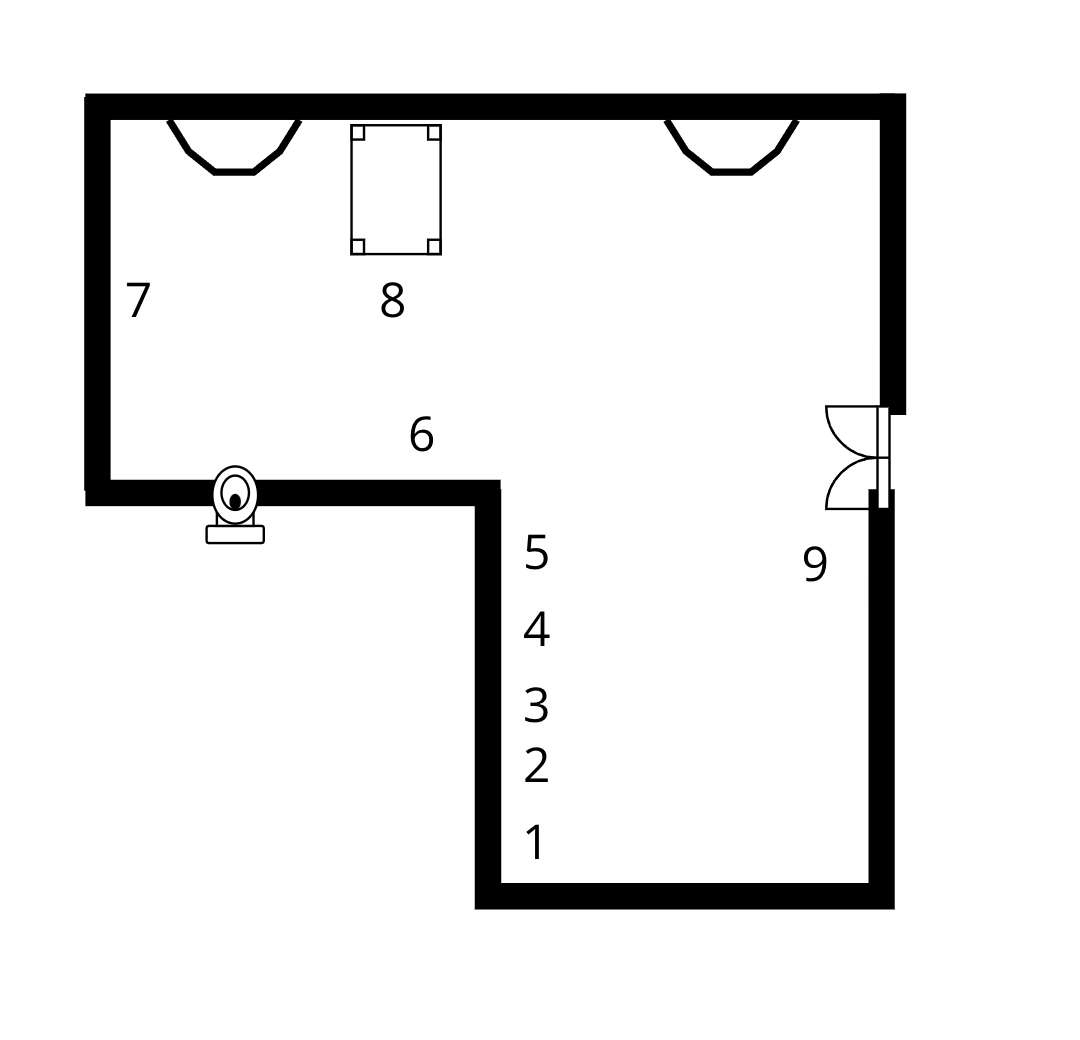

Otto Bremer Room Gallery Map

1. Letter from Emily Bremer, 2022

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

2. Letter from Edward G. Bremer, 2022

Mixed Media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

3. Edward Bremer’s Portrait of Betty, 2022

Paint, pencil, and tape on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

4. Schmidt Brewery and We’re Glad You’re Here Coasters, 2022

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

5. Letter Home From Camp (Edward), 2022

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

2. Letter from Edward G. Bremer, 2022

Mixed Media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

3. Edward Bremer’s Portrait of Betty, 2022

Paint, pencil, and tape on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

4. Schmidt Brewery and We’re Glad You’re Here Coasters, 2022

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

5. Letter Home From Camp (Edward), 2022

Mixed media on paper

18 inches by 24 inches

6. Bob Johnson For Governor, 2022

T-shirt and photograph

11 inches by 14 inches

7. The Saint Paul Winter Carnival, 2022

Digital Video

Duration: 11:19 minutes

8. Schmidt Marching Band Uniform, 1917

Wool suit with two woolen hats and buttons

Dimensions vary

9. I am the…, 2022

Pencil and pen on paper with fabric

11 inches by 14 inches

T-shirt and photograph

11 inches by 14 inches

7. The Saint Paul Winter Carnival, 2022

Digital Video

Duration: 11:19 minutes

8. Schmidt Marching Band Uniform, 1917

Wool suit with two woolen hats and buttons

Dimensions vary

9. I am the…, 2022

Pencil and pen on paper with fabric

11 inches by 14 inches

The Glass Display Cabinet located inside of the Welcome Center contains family memorabilia from the Schmidt Brewery and Winter Carnival.